Lumen

The genesis of the Lumens series is deeply entwined with the artist’s own history. A descendant of an ancient Jewish family from the island of Djerba, Benaïnous began the early 2000s with an ecumenical internet project aimed at fostering dialogue among the three Abrahamic faiths. This initiative brought him into close conversation with leading religious figures: Chief Rabbi David Messas of Paris, Rector Dalil Boubakeur of the Grand Mosque of Paris, and Father Patrick Desbois of the French Episcopal Committee for Relations with Judaism.

It was through Father Desbois’s groundbreaking work on the “Holocaust by Bullets” that Benaïnous became involved in documenting the first sites of Nazi mass executions across Poland and Ukraine, collecting final testimonies from witnesses to these atrocities. Then, in April 2002, while visiting Djerba during the terrorist attack on the Ghriba Synagogue, David captured an image that would echo across the world: a sacred book, blown open by the blast, resting on Psalms 13 and verses traditionally recited after surviving a violent death. This photograph became a silent witness to both fragility and faith.

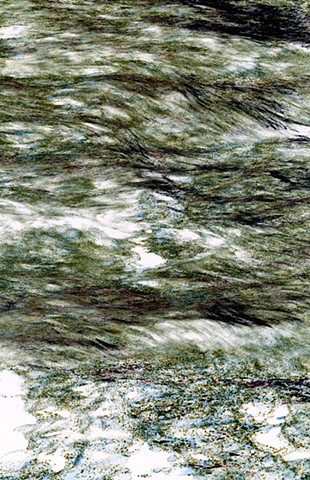

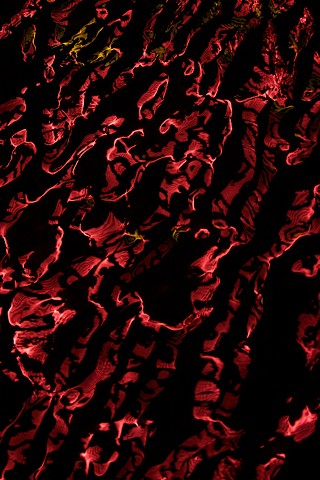

Immersed in traumatic histories and buried memories, Benaïnous felt the limitations of figurative representation. He began seeking a visual language that could convey raw emotion without relying on literal depiction—a way to inscribe feeling directly onto film. During a final winter journey with Father Desbois in 2004, the first Lumens emerged.

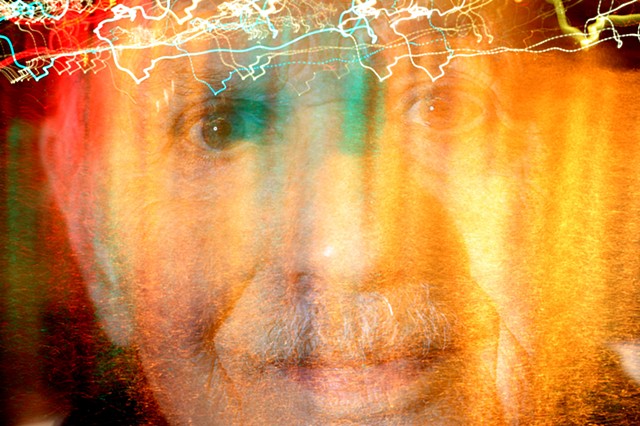

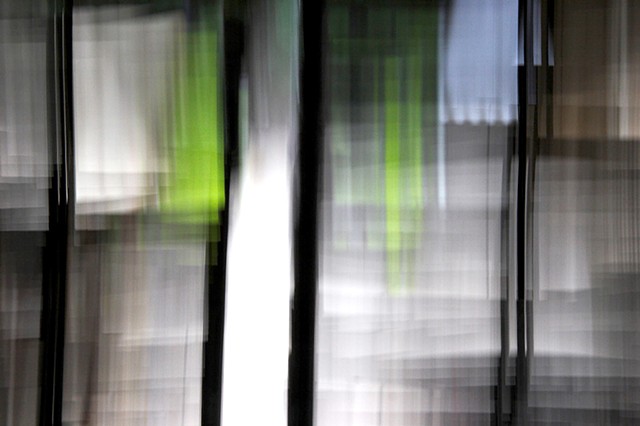

Influenced by Zen in the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel, Benaïnous adopted an approach in which technical control gives way to intuitive release. The camera becomes an extension of the self—or perhaps, the self recedes entirely, allowing the unconscious to take the lead. He describes this state as “shooting in spirit”: a visual meditation where the ego dissolves into presence. The resulting images often possess a tremulous, vibrating quality—evoking impermanence and suspended time.

These are not simply photographs. They seem to occupy a fourth dimension—one of emotional movement, of metaphysical resonance. Are the Lumens without subject?

Without form? Their subject is not fixed, but fluid—atmospheric, layered, emerging from light and shadow like echoes of voices and vanished places absorbed by the artist.

Here, the Dionysian overwhelms the Apollonian. Benaïnous moves beyond photography’s traditional documentary function to embrace what André Breton called “convulsive beauty”—a beauty that must unsettle to be true.

The Lumens are not images of something.They are experiences in light—vessels of memory, reverence, and rupture.